The Buildings of Clermont Farm

Explore the grounds of Clermont Farm and discover the stories held within its historic buildings and landscape. Set on 360 acres in Clarke County, Virginia, Clermont is dedicated to education, preservation, and community enrichment. From the Main House to the Spring House, Slave Quarters, Barn, and more, each structure offers a glimpse into the people, practices, and history that shaped this working farm.

Explore the Grounds.

Learn About the Farm.

Main House

The Clermont Main House is one of Clarke County’s oldest and best-preserved 18th-century homes. Built in 1756 by Thomas Wadlington as a frontier dwelling, the house has evolved over time through thoughtful modifications that reflect changing ownership and personal histories. Over 257 years, it remained in the hands of just three families and their descendants, reaching its current form in 1971 under the McCormick/Williams family. The earliest sections of the house feature architectural elements common to 18th-century homes in Virginia’s Piedmont and Tidewater regions, shaped by the Anglo-American building traditions of Clermont’s original English and Scots-Irish owners. Later additions continued these methods, resulting in a rare and layered example of vernacular architecture.

Spring House

The Spring House at Clermont Farm, built around 1856–1857, reflects the continued prosperity of the McCormick family’s farming operations during the mid-19th century. Located near Dog Run, a tributary of the Shenandoah River, this structure served as a natural refrigeration space, where cool spring water helped preserve perishable food. Dendrochronology reveals the use of timbers from earlier buildings, adding to its layered history. Included in Clermont’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places, the Spring House is a rare surviving example of its kind. It is currently being stabilized with support from a $472,000 Semiquincentennial Grant from the National Park Service.

Landscape

Clermont Farm’s 360-acre landscape offers a living example of the rural farm experience, with open fields, gentle rolling hills, and long views of the Shenandoah Valley. As a working farm, the land is divided into multiple fields and pastures that reflect its agricultural roots. Conservation efforts are underway to protect and restore the natural environment, including removing invasive plant species and planting native trees to enhance habitat and biodiversity. Wildflowers bloom across the property, and native limestone boulders dot the fields, adding to the scenic character of this historic Virginia landscape.

Slave Quarters

The Slave Quarters at Clermont Farm is a rare surviving example of early 19th-century housing for enslaved workers. Built in 1823, the one-story log structure features a continuous stone foundation, steep gable roof, and a central brick flue. Originally consisting of two rooms heated by stoves, the building was later modified to serve the needs of hired workers following the Civil War. Though much of the exterior is now clad in board-and-batten siding, the original log construction is still visible in several areas. Interior walls retain traces of whitewash, offering a glimpse into past living conditions. Today, the building stands as a powerful reminder of the lives and labor of those who were enslaved at Clermont.

Smoke House

The Smoke House at Clermont Farm, built in 1803, is one of the property’s best-preserved original structures. Set on a stone foundation, this square, timber-frame building features a steep pyramidal roof, beaded weatherboard siding, and carefully detailed cornices that echo the craftsmanship of the Main House. Functional design elements include high wall vents for airflow and a central doorway fitted with a board-and-batten door on strap hinges. A wooden aviary tucked beneath the roof’s overhang is likely an early, possibly original, feature. With few alterations over more than 200 years, the Smoke House remains a remarkable example of early 19th-century agricultural architecture.

Main Barn

Built in 1917, the main barn at Clermont Farm was a two-story, timber-framed bank barn constructed with circular-sawn wood and pegged joinery. It featured vertical siding, a standing-seam metal roof, and one-story extensions added in 1918, which connected the barn to a mid-19th-century corn crib. Inside, the upper level included granaries in three corners, while the lower level housed livestock pens with hay mows and feeding troughs. Two silos stood nearby, along with a large water cistern beneath the west ramp. A fire in 2018 destroyed the barn, corn crib, and a rare archaeological artifact—the forebay and turbine boxes of a 19th-century “tub” mill (horizontal water wheel), similar to some once used in the area to grind Clermont wheat. The loss was a powerful reminder of the farm’s long-standing connection to and dependence on its eternal context: regional markets, milling industries, and transportation networks.

Corn Crib

The Corn Crib at Clermont Farm, built in 1849 by Edward McCormick, is one of the earliest structures he commissioned after inheriting the property. Raised on stone piers and later reinforced with 1920s concrete supports, the structure was capable of holding more than 1,200 bushels of ear corn—nearly the entirety of McCormick’s 1850 crop.

Used actively for over a century, the Corn Crib played a central role in sustaining Clermont’s livestock operations well into the 1960s. Severe storm damage in 2017 threatened its survival, but a major rehabilitation effort completed in 2018 stabilized the structure and restored it for continued use in feed storage and preservation education. Six months after the rehab, in November 2018, the building burned down along with the entire 1917 barn. Today, the Corn Crib pillars remain and are used as a powerful reminder of the cycles of labor, production, and care that have defined Clermont’s farming history for more than 170 years.

Corn Crib in 2018, following the building rehab.

The remaining stone foundation in 2024.

The cemetery at Clermont Farm is a 55-by-35-foot stone enclosure confirmed in 2010 by state archaeologists to be a burial site. Preliminary testing identified at least five graves, marked by uninscribed field stones placed at the ends of burial shafts. The total number of burials remains unknown. Artifacts such as handmade iron nails and a silver-washed metal button suggest the cemetery was in use in the second half of the 18th century. While the identities of those buried here are still one of Clermont’s greatest mysteries, the site has long been referred to as the “Snickers Graveyard”, possibly linking it to Edward Snickers and his wife Elizabeth. She died at Clermont in 1779. With no surviving marked gravestones, the burial site may also include enslaved individuals connected to the Snickers family or later owners. The Grace Episcopal Church burial register 1879-1927 includes the infant Ella Williams Jackson, who died June 27, 1884, age two weeks, and was buried at Clermont. The 1880 U.S. Census lists at Clermont “Hanah Jackson”, Black, 35, servant.” Future archaeological research may offer more answers.

Cemetery

Ice House

The Ice House at Clermont Farm once stood about 150 feet east of the Main House and served as a year-round storage site for ice cut from nearby water sources. Today, a large seven-foot-deep depression marks its location, partially filled with wooden structural remains. According to Elizabeth Rust Williams, these materials are remnants of the original structure whose roof collapsed in the 1980s. Though no longer standing, the site provides valuable insight into 19th-century food preservation practices and daily life at Clermont.

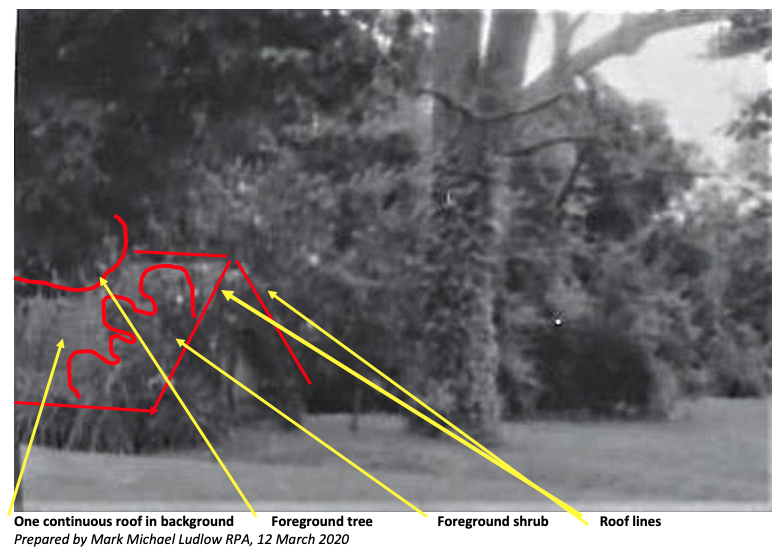

Clermont Ice House Roof Lines (background detail from a ca. 1958 photo of a McCormick/Beardall/Pinney family picnic on the east lawn of the owner's house at Clermont.) This low-roof structure over the sunken Ice House closely resembles the restored one at Belle Grove Plantation, Middletown, VA.

The buildings at Clermont Farm are undergoing a long-term stabilization process guided by the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the treatment of historic properties. In keeping with the farm’s educational mission, the chosen approach is “Preservation”—retaining and protecting all historical layers and periods of significance. Unlike restoration to a single era, reconstruction from scratch, or rehabilitation for modern use, this method allows the buildings to remain authentic teaching tools. Most structures are empty, have been dated through dendrochronology, and are open for research and instruction in historic preservation and related fields. A $472,000 Semiquincentennial grant from the National Park Service is currently funding repairs to three of the site’s historic buildings.